How shocked will you be to learn that adding a steam tunnel can actually increase your labor cost? I have a pair of stories to tell you about Steam Tunnels. The makers of these tunnels could already be poised to shoot me, but I promise that I have recommended them many times and I may be responsible for more sales of steam tunnels than some of their salesmen. However, the fact remains that what is good for one cleaner is bad for another. People doing fire restoration work, for example, should always have a Steam Tunnel. Some decision makers in this business think that they can benefit from what their peers do and simply copy them and thereby cut through all of the red tape known as due diligence. What did George Carlin say years ago, mimicking somebody’s mother? “I suppose that if Johnny Finnegan jumped off the Empire State Building, you would have to jump off the Empire State Building!” Free advice is worth exactly what you pay for it.

A client purchased a used steam tunnel for $8000 with the endorsement of his peer group. When I was last at his plant, the machinery was yet to be installed. I knew that when I would return there the following year, the tunnel would be in operation. I had no idea what would become of my fact-finding and analysis, but as a pro-active manager, I wanted goals, expectations and forecasts. I was quite surprised at what I found. I will get into what I found and how in a minute, but the really important part of this experience is how I got to prove the tunnel experience both ways; adding a tunnel and costs go up and then later deleting a tunnel and costs go down. To be clear, remember that this is not tunnel-bashing. It is hardly a lesson in not investing in your business. It is a lesson in analyzing your costs. Your results could differ. There were a few unique features about the client that had just bought a tunnel:

▲ His pressers were on piece pay. This would prove to be very beneficial in assuring accuracy in our findings

▲ His pressers average 43 pieces per hour per presser – excellent productivity. There were 6 pressers

▲ He had excellent records. Plenty of data. This was partly because he is a good operator and partly because he was paying pressers by the piece. Therefore he had to have a record of pieces.

▲ This is a busy plant.

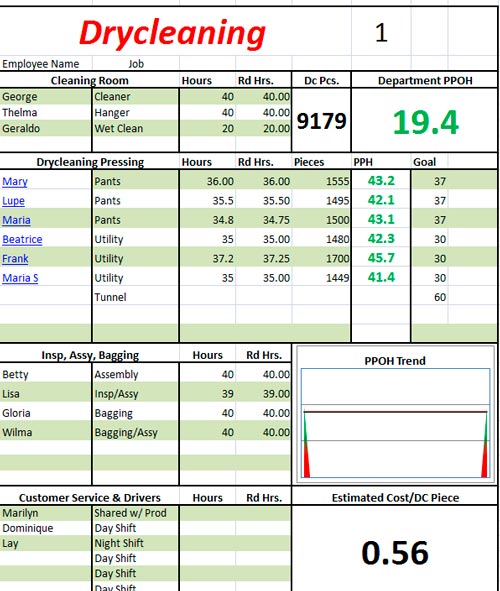

Following is a mock-up of this plants PPLH numbers for a typical week.

The labor cost per piece in this scenario is 56 cents per piece when the average hourly rate is $10.87. The three utility pressers are the ones that do pieces that would go to the tunnel when that tunnel is put into service. Let’s guess-timate that two out of ten utility pieces are items that could be tunneled and then need no further pressing or touch-up. This includes sweaters, scarves, jackets, coats, etc. The oft forgotten thing about a tunnel is that the easy pieces – the gravy, so to speak – is taken away from the pressers! They can no longer produce the numbers that they had previously attained! Understanding this is of paramount importance. What your pressers will actually produce now is probably not too much more than an educated & informed guess. One thing is certain: The productivity will be measurable less than what they are attaining now, without question. Let’s come up with an “educated and informed guess.”

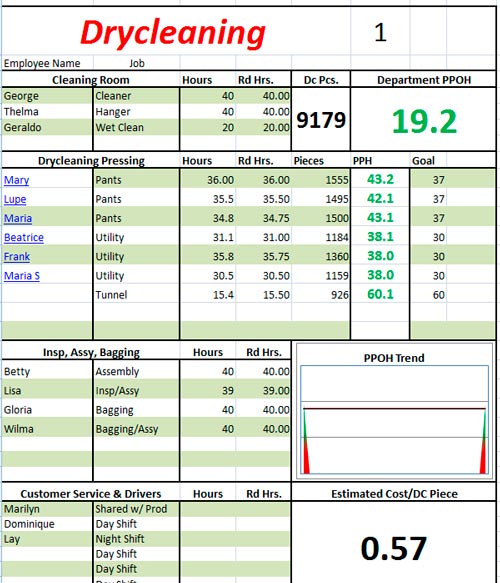

Beatrice currently presses 43 pieces per hour. It takes her an average of 84 seconds to press each piece. But 8 of those pieces are really easy pieces, so let’s say that it takes her half the time to do those 8 pieces. This means that it takes 42 seconds to do 8 of the pieces. She has 35 additional pieces to do that hour and, therefore will spend 93 seconds on each of those pieces. Got that? It really takes a minute and a half for each piece, but because of the easy pieces that she can bang out in half the time, she gets great productivity. If we remove the easy pieces, every piece will take 93 seconds to press and reduce Beatrice’s pieces per hour to 38. That is an 11.6% reduction in productivity. How’s that for an “educated and informed guess”? Now let’s look at my production spreadsheet again. In this example, the utility pieces pressed by the utility pressers has been reduced by 20%, a tunnel operator has been added and the presser’s productivity has been reduced to 38 pieces per hour from 43. You could make an argument that one of the utility pressers would become the tunnel operator but that does not help mathematically. The utility pressers would work significantly more hours and would work many more hours than the pants pressers, and the assembly/inspection people would work longer. So now my production spreadsheet looks like this:

So now we have added a tunnel and another employee for a mere 15 hours per week and raised our cost per piece one cent. Not impressive. However, we are far from done:

▲ In this example, the pressers were paid by the piece. This is very important because it assures accurate figures. If they were paid hourly, they would be very likely to “pad the time clock” and take the same amount of hours to do 20% fewer pieces. Not so in this case. They were paid by the piece. No more pieces = no more money.

▲ The pressers have just lost 20% of their pay and they can’t make it up by dragging out the day. Result: disgruntled pressers. Disgruntled pressers are part of life if you are the big winner as the owner. But consider that you have spent money on a tunnel, paid to install it, pay every day to feed steam to it and have these disgruntled pressers, all so that you can increase your cost a penny per garment.

▲ At 9700 pieces per week, every week, that $4700 per year. All so that you can have a tunnel?!

But wait! There’s more! The 3 utility pressers have seen their hours reduced. Let’s assume that they are hourly employees for now. You could use one of them to run the tunnel. They would get their hours and you would get, uh…., oh yeah, a tunnel. So now, you have all of the above “benefits” (?), but not the disgruntled pressers part. My experience has shown that you won’t do it this way. Here’s why: you have two 90-pound drycleaning machines. In them are 180 pieces. Of those, 72 are pants. Of the remaining 108 utility pieces, 22 can be tunneled. It takes 75 minutes to clean 22 pieces that can be tunneled. The biggest problem with a tunnel is that there are not enough pieces to do! If the drycleaning department cleaned all 9179 pieces before the pressers came in for the week, all 926 pieces could be sent through the tunnel at once, perhaps at the rate of 175 pieces per hour. This means that all of the tunnel-able pieces for the week could be done in about 5 and a quarter hours. This is a practical impossibility for many reasons, but even if it were not, saving ten (theoretical) hours would have very little affect. The volume of pieces, by the way, is the reason that a tunnel works so well for those doing restoration work.

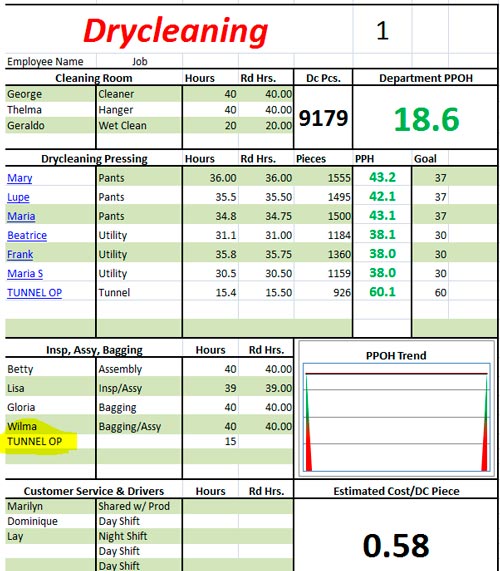

Based on my experience, what would happen: you would have a full time tunnel operator that your run the tunnel for 15 hours per week and then “help” the inspection department for another 15 hours per week so that her hours would approximately equal that of the pressers. My spreadsheet would look like this:

We have increased our cost per piece by 2 cents and lowered our Pieces Per Labor Hour from 19.4 to 18.6. This does not mean that this will be true for you, but it could be. The conventional wisdom is: “I’ll replace a presser doing 35 pieces per hour with a tunnel that does 75 pieces per hour. It is an obvious ‘can’t lose’ situation!” Hmmmm.

Last month, I was with a regular client that has had a tunnel for years. There was always some sort of productivity issue there, but I never suspected the tunnel until I experienced what I just described. This time it was far easier to test what it would be like run without the tunnel. We simply did not staff it and sent all of the easy pieces to the under-producing pressers. Result? PPLH increased a stunning 20%! I was as amazed as everyone else.

Myth busted?

Myth busted?

“If you do what you always did, you’ll get what you always got.”

Donald Desrosiers

Don Desrosiers has been in the laundry and drycleaning industry for over 30 years. As a management consultant, work-flow systems engineer and efficiency expert, he has created the highly acclaimed Tailwind Shirt System, the Tailwind System for Drycleaning and Firestorm for Restoration. He owns and operates Tailwind Systems, a management consulting and work-flow engineering firm. Desrosiers is a monthly columnist for The National Clothesline, Korean Cleaners Monthly, The Golomb Group Newsletter and Australia's The National Drycleaner and Launderer. He is the 2001 winner of IFI's Commitment to Professionalism Award. He has a website at www.tailwindsystems.com and can be reached at tailwindsystems@charter.net or my telephone at 508.965.3163