“That’s not fast enough,” he said. More than 2.3 million people around the world have died, and many countries will not have full access to the vaccines for another year or two: “Fast — truly fast — is having it there on day one.”

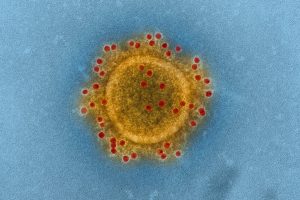

There will be more coronavirus outbreaks in the future. Bats and other mammals are rife with strains and species of this abundant family of viruses. Some of these pathogens will inevitably spill over the species barrier and cause new pandemics. It’s only a matter of time.

There will be more coronavirus outbreaks in the future. Bats and other mammals are rife with strains and species of this abundant family of viruses. Some of these pathogens will inevitably spill over the species barrier and cause new pandemics. It’s only a matter of time.

Dr. Modjarrad is one of many scientists who for years have been calling for a different kind of vaccine: one that could work against all coronaviruses. Those calls went largely ignored until Covid-19 demonstrated just how disastrous coronaviruses can be.

Now researchers are starting to develop prototypes of a so-called pancoronavirus vaccine, with some promising, if early, results from experiments on animals.

After coronaviruses were first identified in the 1960s, they did not become a high priority for vaccine makers. For decades it seemed as if they only caused mild colds. But in 2002, a new coronavirus called SARS-CoV emerged, causing a deadly pneumonia called severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS. Scientists scrambled to make a vaccine for it.

The danger of coronaviruses became even clearer in 2012, when a second species spilled over from bats, causing yet another deadly respiratory disease called MERS.

Many researchers started to wonder if making a new vaccine for each new coronavirus — what Dr. Modjarrad calls “the one bug, one drug approach” — was the smartest strategy. Wouldn’t it be better, they thought, if a single vaccine could work against SARS, MERS and any other coronavirus?

That idea went nowhere for years. MERS and SARS caused relatively few deaths, and were soon eclipsed by outbreaks of other viruses such as Ebola and Zika.

In 2016, Maria Elena Bottazzi, a virologist at Baylor College of Medicine, and her colleagues applied for support from the American government to develop a pancoronavirus vaccine, but did not receive it. “They said there’s no interest in pancorona,” Dr. Bottazzi recalled.

Three years later, a third dangerous coronavirus emerged: the SARS-CoV-2 strain that causes Covid-19. Although this virus has a much lower fatality rate than its cousins that cause SARS and MERS, it does a far better job of spreading from person to person, resulting in more than 106 million documented cases around the world and still climbing.

Although the Covid-19 pandemic is still far from over, a number of researchers are calling for preparations for the next deadly coronavirus.

“This has already happened three times,” said Daniel Hoft, a virologist at Saint Louis University. “It’s very likely going to happen again.”

So far, research data is promising.

- Virus-like shell studded with spike proteins from the three coronaviruses that caused SARS, MERS and COVID-19 created antibodies in mice that worked against all three coronaviruse. Some of those antibodies even worked on a fourth human coronavirus even though its spike protein was not used.

- In another research, a vaccine with spike proteins from eight different coronaviruses created antibodies in animal testing that worked on not only those eight viruses but also four other viruses that were not used in the vaccine.

- Dr. Modjarrad is leading a team at Walter Reed developing another vaccine based on a nanoparticle studded with protein fragments. They anticipate starting clinical trials on volunteers next month.

- Dr. Hoft of Saint Louis University has created a vaccine that prompts cells to make surface proteins that might alert the immune system as if a coronavirus — any coronavirus — were present.

The search for a pancoronavirus vaccine may take longer than our expectations. But even if it takes a few years, it could help prepare the world for the next coronavirus that jumps the species barrier.

The search for a pancoronavirus vaccine may take longer than our expectations. But even if it takes a few years, it could help prepare the world for the next coronavirus that jumps the species barrier.

“I think we can have vaccines to prevent pandemics like this,” Dr. Memoli, a virologist at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said. “None of us wants to go through this again. And we don’t want our children to go through this again, or our grandchildren, or our descendants 100 years from now.”